Discriminatory Covenants

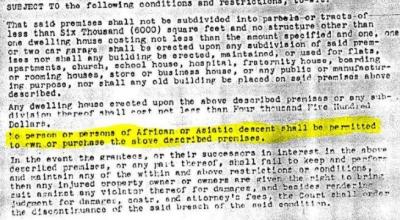

Deed restrictions such as Covenants, Conditions & Restrictions (CCRs) are commonly known today for laying out rules for homeowner's associations. However, those who own older residential property may also find racial restrictive covenants in their property deed and CCRs.

The Civic Unity Committee, in a 1946 publication, defined racial restrictive covenants as: “agreements entered into by a group of property owners, sub-division developers, or real estate operators in a given neighborhood, binding them not to sell, lease, rent or otherwise convey their property to specified groups because of race, creed or color for a definite period unless all agree to the transaction.”

History of Racial Restrictive Covenants

Racial restrictive covenants began in the mid-19th century and were recorded when a lot was created, when a subdivision was approved, or when a home was built. Later, during the Great Depression, the National Housing Act of 1934 was passed with the intention of keeping banks from exceeding their loan reserves. Banks responded with the practice of redlining. Redlining identified areas on city maps where bank investments and sales of mortgages where preferred and redlined areas where lenders were discouraged from financing properties. This practice ultimately provided financial incentives to include racial restrictive covenants while also refusing financing to people of color in the only neighborhoods they were allowed to purchase. This type of systemic racism became widespread across America; prohibiting the building of wealth through homeownership and deepening segregation based on race, color, and creed.

The Supreme Court found racial restrictive covenants to be legally unenforceable in 1948 based on the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The ruling established that courts would not enforce the covenants but did not prohibit the inclusion of racial restrictions in covenants or prevent private enforcement. It was not until the passage of the Federal Fair Housing Act of 1968 that the racial restrictive covenants became illegal. This means that those who own residential property built before 1968 could very likely find language in their own CCRs that reflects our history of exclusion in housing.

National Homeownership Trends

Over 50 years have passed since racial covenants became illegal, but the nation continues to see significantly different rates of homeownership for various racial groups. Fair Housing compliance checks across the country also continue to identify real estate transactions where racial bias limits access for renters and homeowners. In 2020, the U.S. Census Bureau reports the following homeownership rates among Americans:

- White | 76%

- Asian, native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islanders | 61.4%

- Hispanic | 51.4%

- Black | 47%

While racial restrictive covenants are not enforceable, the presence of the language has made its way to the Oregon State Legislature. In 2018, the Legislature passed two laws - ORS 93.270 & ORS 93.274 - that are intended to make it easier for property owners to remove racist provisions from the title of their property through State Circuit Courts.

Learn More

Those who would like to learn more about a specific property's history and the process to remove racial restrictive provisions can find more information below.